by Josh Morrison | Aug 22, 2016 | Uncategorized

Back in June, I, like so many Americans, was shocked and horrified at the awful tragedy at Pulse Nightclub in Orlando. So many innocent lives lost in the latest mass shooting in the United States! A massacre so devastating, that it has brought together those who previously disagreed on the nations’ gun laws. A step in the right direction!

As I pondered the loss of innocent lives and prayed for the families affected by the carnage, I couldn’t help but think of the kidney patients who die every day waiting for transplants. The number of people killed in Orlando would be similar to the number of kidney patients dying every 2 to 3 days. Isn’t it shocking!

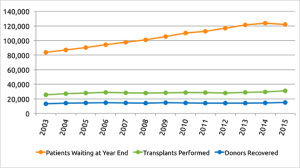

The truth is, the gap between those on the waiting lists and the number of transplants performed annually in the United States keeps growing by the thousands. For the past 5 years the number of transplants have remained flat and the need multiplies. I wonder who is noticing these figures and finding solutions to this problem. Is there a shortage of kidneys? The answer is a simple NO!

Let me share a recent story. To protect the subject’s privacy, we will call this “Miriam’s story”. Miriam is a senior citizen who has recently retired. Over six months ago, I was approached by her daughter to help Miriam get a kidney transplant. However, there was no further contact until Miriam was in emergency and was admitted to receive dialysis in the hospital. Miriam was in serious condition and was in the hospital for several days. After her release from the hospital Miriam went for dialysis at the local dialysis center. I felt it was strange that Miriam had not been dialyzed earlier at the dialysis center.

On further inquiry, I was informed by Miriam’s daughter, that her nephrologist had told her, “if she started dialysis it would hurt her chances of receiving a kidney transplant”. This wasn’t the first time I had heard this sort of precautionary tale. It was time to check with those who should know about these things. When I inquired I was informed, “this is not true and further education needs to be provided for the nephrologist through the local CMS network”. Lesson learned – double check and get a second opinion or you may find yourself in the emergency room of a hospital.

Miriam had received a fistula several months before she went into the dialysis center. Therefore, she was ready to receive dialysis through a fistula. This was good news. However, she was in severe pain when the needles were inserted. After, speaking with Miriam’s daughter regarding using Lidocaine, I was informed that the dialysis center would not give Miriam Lidocaine shots. After speaking with the Administrator of the dialysis center, I was told the manager would not allow these shots for Miriam. Having been in dialysis for 50 months, where I received Lidocaine shots every time, I find it strange the same cannot be given to Miriam.

Now came the time to find living donors for Miriam. I was pleased to learn 5 extended family members had applied to be donors for Miriam. However, during the past 6 months no progress had been made to test the potential donors. It was time to speak with the living donor coordinator. After explaining my story and the work Living Donor Outreach does in educating the transplantation community to increase donors, the coordinator agreed to speed up the process. Lesson learned – must stay on top and don’t wait for things to happen by themselves!

True to her word, the coordinator sped up the process and rejected all five donors within a month! Shocking one would say! She rejected the potential donors on the basis of family history of diabetes! None of them had diabetes. We asked for a copy of the protocol from the institution. We were provided a slide presentation, which did not reject donors because of a family history of diabetes. They were not following their own protocol. Lesson learned – beware of cherry pickers! They will let you die!

We could have fought the decision, but we thought it better to contact other centers around the country and locally to get a second opinion. Other living donor coordinators told us they would not reject a living donor because of family history of diabetes but will test the candidates and possibly have some extra tests. Lesson learned – get a second opinion! It may save your life!

Here’s the irony! The center that rejected the potential donors, requested my program, “Proactive Education for Family & Friends” to train their medical students 9 months ago. hopefully to increase living donors.

Today, Miriam’s health records have been sent to the new transplant center and we have been told everything is on track. They will contact us if they need any further information. Lesson learned – Don’t give up!

This is just one recent case, among many, of ESRD patients finding it difficult to maneuver through the system to receive a transplant. After extensive research, we have found a lack of education, at all levels, is a major problem afflicting the transplantation community to increase donors. Although Miriam’s daughter and other members are in the medical field they found it difficult to do the right thing for their mother. They said, “Thanks for helping us, we were lost!”

by Josh Morrison | May 3, 2016 | Uncategorized

About four years ago, I donated my kidney to someone I didn’t know. Today I work in the transplant field for a living, so being a donor comes up a lot. It’s basically the first thing most people find out about me.

Which I really hate, to be honest: I don’t like seeming different, like people assume I’m some sort of saint. That’s not how I see myself. It’s not how I want others to see me.

On top of that, every time someone asks me why I donated (which is always), I never really know what to say.

It’s not that I lack for explanations. I’ve dissected my decision to death. The explanations I give tend towards the clinical—causal factors explicating my aberrant behavior. I’d had anesthesia before; I overemphasize abstract reasoning and principles; I went to Catholic school; I have a savior complex, etc.

That doesn’t include the jokes I tell because explaining makes me nervous: “I was a corporate lawyer and wanted the time off.”

But that just list traits like I’m talking about someone other than myself. Mix that with the humor, and it’s just a way to pretend I’m in the same spot as my interrogator: “I know it’s weird too.”

That hides the way I really feel about it, hides my earnestness. I gave because if I didn’t someone would die. None of my other reasons matter.

It didn’t need to be my responsibility. No one’s ever obligated to be a kidney donor, to anyone, for any reason. I chose to take that on myself.

For most donors, giving a kidney fulfills a need closer to home – saving the life of someone they care about. But there too, I think an essential step is to assume a responsibility that you have every right to walk away from—choosing to voluntarily burden yourself with the needs of another; choosing to answer that need by sacrificing of your own body.

We live in a transactional culture where we’re told always to put yourself first. Don’t take on burdens that aren’t yours. No one’s entitled to your help. Look out for number one.

That makes discussions about giving an organ really difficult. It feels like people often take living donation as an indictment of their own choices—if you don’t know whether you’d give a piece of yourself to save a friend’s life, does that make you a bad person?

Of course not. No one needs to take on obligations that aren’t theirs. But, for me, the choice to accept responsibility enlarged my own life, made it richer with purpose. Becoming a kidney donor was the best decision I ever made. It made me happier than anything else I’ve done in my life.

I’d wanted to donate for years. When I finally did, it felt like running my first half-marathon or graduating from law school. It was an achievement I’d deliberately planned and had to work to make happen, like summiting my personal Mt. Everest. I had gotten the chance to live out the best version of myself.

For many people, donation only deepens their sense of self—confirms the potential they knew they had all along. Many see it in practical terms: when someone I cared about was in need, I merely answered the call. They go back to their lives feeling joyous but largely unchanged.

That’s not what it was like for me. The experience turned out to be addictive. I had been working in a job that meant nothing to me besides the paycheck. Suddenly I felt drawn to a higher calling, though I didn’t yet know that meant working to end the transplant shortage. When I donated, I had set my mind and accomplished something profound. Now that I knew I had that power, I couldn’t just go back to the compromises I’d been making.

The road to where I’ve ended up was a long one. I tried to be a writer and failed at it. I left my home and the woman I lived with to start a new career in Toledo, Ohio. (I didn’t know anyone within two hundred miles). I received a grant, came back to the east coast, and started Waitlist Zero.

Ending the kidney shortage is my life. It wasn’t when I donated, but the same feelings that made me a donor then make me want to find everyone a donor now. The same things that make me uncomfortable telling my story as a donor keep me from speaking on my passion for Waitlist Zero.

Waitlist Zero means finding a transplant for everyone who needs one. It means that access to medical care shouldn’t be contingent on your skin color or your health insurance or how many friends you happen to have or how healthy they happen to be. It means that no one should ever have to feel the loneliness of wondering if anyone cares about you enough to save your life. It means tens of thousands of families each year shouldn’t have to go to someone’s funeral and wonder if they could have done more.

I wish I could say that this passion for ending the shortage was broadly shared but it’s not—for the simple reason that most people in the field don’t believe it’s even possible. Doctors are passionate about caring for their patients—incredibly passionate. But for decades the shortage has been growing and growing and the number of transplants has just stayed the same.

It gets tiring to hit your head against the same wall; after a while you forget that anything better exists. It’s hard to expect faith in the possibility for change.

But I do have that faith. It’s what sustains me through the travails of starting a new business and feeling sometimes like I’m making every possible mistake along the way. And I could give a dozen reasons why ending the shortage is possible: how living donation saves the government hundreds of thousands of dollars per patient; how studies show educating patients and their families can nearly double the rate of living donation; how if only one in ten thousand Americans donated each year, there’d no longer be a shortage.

Right now, six in seven people who need a transplant can’t find a living donor—I refuse to accept that six in seven Americans don’t have someone able and willing to save their life if only our community did a better job of supporting donation.

Yet those are just rational reasons. Ending the shortage is a transformational change: something more is needed than mere logical deduction. Otherwise it would have happened already.

What drives me to keep going is less rational certainty than the conviction that the field needs at least one person who believes the shortage can be defeated—the hundred thousand patients on the waiting list deserve champions who refuse to accept their deaths as inevitable. And we deserve a community where people take responsibility when they don’t strictly have to, a community that supports transplant and never lets die somebody who only needs a willing donor to live.

.

by Stephen Rice | Apr 5, 2016 | Uncategorized

Eight years ago, Josh Morrison was in law school and doing what one often does while in school – reading. While most of his time was spent reading case law, in the fall of 2007 he happened to come across an article about a woman who needed a kidney. He was struck by the safety of the procedure and the fact that one could save a life without much impact on his or her own health. More than that, he was struck by the plight of the woman. She’d had three possible donors, but all three backed out. He empathized with the thought of being in that situation – having to test out whether his friends or family liked him enough to give one of their organs. He imagined what it would be like to have to beg for his own life.

He didn’t act, but the article had planted a seed.

A year passed and Josh found himself staring at another article on the subject. This time it was about a Good Samaritan donor. He decided that he wanted to do it. He did his research, but his wife at the time was very uncomfortable with it. When they divorced for other reasons two years later, he was able to pick up the list of things he wanted to do. Donating a kidney anonymously rose to the top.

Josh’s hope was that he would be able to initiate a donor chain. It looked as if he’d be able to start a chain of five-to-six donations. “It fell through. The hospital only did chains once a month, and I didn’t have the ability to take more time off of work so I donated to the next person on the list,” said Josh.

That ‘next person’ happened to be J.D. Mendes, also from Boston. J.D.’s kidney failure had come out of the blue. He didn’t know that he had kidney disease until one day he collapsed. He was in so much pain that he thought he was dying. JD spent the next eight years on dialysis – eight years waiting for a new organ to become available.

Four months after their surgeries, Josh and J.D. were able to meet. The meeting took place at the transplant center. Several social workers were present, plus JD’s mom. “It was very emotional,” recalls Josh. “He’s an eloquent and charismatic story teller and he told me his story. It was one of the most profound experiences of my life.”

Asked to reflect on the experience, Josh said, “the most satisfying part was the experience of achieving something great that I could have given up on, but didn’t. I felt like other achievements would be possible.” Josh feels that many times, others don’t understand his motivations. “There’s nothing better about me than anyone else. I think I’m pretty normal, but others’ reactions can make me feel very different sometimes,” explains Josh.

Josh’s advice for patients and potential donors is both practical and insightful. On the practical end, Josh recommends using an abdominal binder during recovery. “Don’t lift a lot of weight because you’ll get a hernia. And have some food frozen in the house.” Josh adds, “For those considering becoming a Good Samaritan donor, think about starting a chain.”

Josh’s more insightful advice is for patients. “I once spoke to a person on dialysis who described to me the many funerals she’d attended for people who’d also been on dialysis, but who didn’t seek out a transplant. It must be a horrible feeling for family members to think ‘I could have done more.’ Please talk to family members about it. It’s not just the patient who benefits. It’s the whole family.”

by Stephen Rice | Feb 12, 2016 | Uncategorized

While in college, Raegan Johnson’s mom started dialysis, but Raegan didn’t really know what it all meant. She knew her mom had lost a lot of weight, and that she was receiving treatment, but Raegan didn’t make the connection that her kidneys were failing. Her mom was very reluctant to ask a loved one to become her donor and had refused an offer from Raegan’s aunt. At age 24, Raegan’s older brother learned from his doctor that excess proteins had been found in his urine. He had been diagnosed with the disease too.

Fast forward six years. Raegan was preparing for graduate school when her brother, Reggie broke the news. His kidneys were failing. Reggie relayed his options: dialysis, transplant from a diseased donor, or the possibility of finding a living donor. His doctor had encouraged him to try to find a donor before resorting to dialysis, but it was tough for a big brother to ask his little sister to do something so selfless. Reggie’s mom helped broach the subject and Raegan agreed to be his donor – but she had to first consider her own health. “In college, I was very overweight. The first question was whether I’d be healthy enough to do it,” said Raegan.

She had work to do. She needed to get her blood pressure down and lose some weight. She lost 5 lbs., got her blood pressure into the acceptable range, and was declared eligible to donate. Some of those around her were apprehensive, and expressed concerns about the potential outcome of the surgery. “Maybe I was naïve, but I wasn’t too worried because I knew I was doing the right thing. Once I’d made up my mind, I was focused.” Raegan adds that her Christian faith also increased her confidence in her decision – in turn reducing her fears of the worst. “If this is how I was meant to go, then I would go having done the right thing,” she concluded.

Asked about how she felt post-surgery, Raegan’s response was immediate. “It was painful. I hadn’t had children, not even a broken bone. I’d never experienced major pain. It was more shocking than anything.” Her recovery time lasted 6-8 weeks.

Despite the discomfort and initial pain of surgery, her experience continues to be satisfying. “It’s the gift that keeps on giving, seeing my brother thrive and being the husband, the father, and the Christian man that he is. It’s a gift to see him do so well.”

Raegan’s donation also kicked off a journey for her to become a healthier person. “Because I didn’t have much of an appetite, I lost 10 lbs right after surgery. But it was such a blessing for me. I started exercising, making better food choices, and I began to see results.” Her journey has also involved becoming an advocate for kidney disease prevention, especially within the African-American community. She serves as a peer mentor for the National Kidney Foundation and her advice always includes a message to get tested. “We focus on breast cancer, which is important, but kidney disease primarily affects African Americans. Nearly 1 in 3 kidney failure patients living in the United States is African American. My message encourages individuals to get their kidneys tested and watch their diets.” Her advice to potential donors is to focus on making sure that each is in a good position to be a donor. “It’s not just about the recipient’s health. As a donor, your health should also be a priority.”

Twelve years after her surgery, her family is doing great. She’s lost a total of 60 lbs, and continues to lead a healthy lifestyle. Reggie is healthy and is off most of his medications. As for Mom? “After our surgery, my Mom reconsidered my aunt’s offer and was transplanted in 2006.”

This story just keeps getting better.

by Stephen Rice | Jan 28, 2016 | Uncategorized

Diabetes runs in Jill Laker’s family. Her older sister developed type 1 diabetes during her second pregnancy. She managed it well, but stress and other health issues eventually led to kidney failure. Her sister started peritoneal home dialysis and after a three-year wait, she received a new kidney from a deceased donor. At the time, Jill had offered to be tested, but her sister adamantly declined. It was 1993 and living donation wasn’t as mainstream as it is today. The new kidney lasted 9 years. Jill’s sister was back on dialysis – this time hemodialysis three times-a-week at a clinic. Jill offered to be tested again, and her sister again declined.

Jill would sometimes accompany her sister to the dialysis center. She saw first-hand how difficult it was. She continued the conversation about living donation and finally her sister agreed to accept the offer if they were a match.

Both Jill and her brother decided to be tested for compatibility, and both were matches! Life circumstances were better for Jill at the time – her children were grown adults, while her brother and wife were raising their young grandson. It made sense that she become her sister’s living donor. “Family is the most important thing to me,” says Jill. “So it wasn’t a hard decision.”

Leading up to the surgery, Jill admits that she was afraid. And the health evaluation produced a lot of anxiety. At each step in the testing process, she thought to herself, “what if they find something wrong with me? What if I find out I have diabetes? What if I don’t have two kidneys?” She pushed back against this self-talk by spending time online looking for information. “It was calming. I felt reassured that everything was going to be fine.”

While the overwhelming majority of nephrectomies are now performed using the less-invasive laparoscopic technique, Jill’s surgery took place in 2003 when the open nephrectomy procedure was still in regular use. A large six-inch incision was made in order to remove her kidney, making her recovery time longer and more painful. The first couple of weeks were very tough, and pain management was difficult. After about four weeks she started to feel good again. Jill, a Canadian living in Canada at the time, used sick time and was paid in full during her two-month leave from work. She also receives free follow-up testing every year, although she has to travel back North each year to receive it.

Twelve years after her surgery, Jill’s health remains fabulous. She has a little numbness in her back from the surgical incision, but nothing that is a bother to her. “Nothing has changed in my life because of having this surgery. My sister is also incredibly healthy. She’s lived to see her son get married and to know her grandchildren.” Asked what has been the most satisfying part of donating her kidney, Jill immediately responds, “Seeing my sister do so well. Seeing her energy come back, the glow to her skin. I’m a person who values family and [my sister] is still here today. That’s what it is all about.”

Based on her experience with her sister, Jill offers some wisdom to people with kidney failure who receive an offer from someone to be their donor. “Accept it. Give people a chance to do it. Talk to your family and be open and honest about what you are going through. If you can get a living donor, do it. You’ll live longer.”

Recent Comments