Paired Exchange and Donor Chains

Paired Exchange

In some cases, prospective donors aren’t a match for their intended recipient. In these cases, it is possible to find another mismatched donor-recipient pair and “swap kidneys.”

Good Samaritan donors can go to a transplant center and ask to donate to the first person on the waiting list. Non-directed donors can also start a chain of transplants by going to a paired exchange program like the National Kidney Registry or Alliance for Paired Donation, however it works slightly differently. Non-directed donors can donate their kidney to a recipient who has a loved one who would donate to them if they were compatible. In exchange, that would-be donor donates to another recipient with an incompatible would-be donor of her own.

Example Scenario

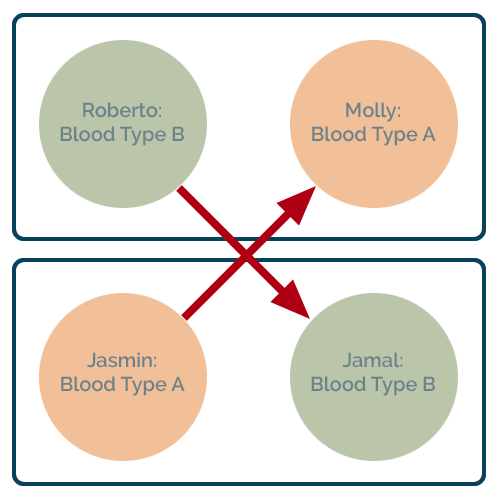

Roberto, blood type A, has kidney disease and just started dialysis, in Phoenix. His friend Molly, blood type B, offers to donate a kidney, but isn’t a compatible candidate. Roberto’s doctor explains another option called paired exchange in which Molly would donate her kidney to another person with a similar dilemma. Molly agrees to the idea. The doctor plugs their health information into a national computer system to identify other possible matching pairs.

The search brings up a number of options, the best being a family living in Dallas – kidney patient Jasmin and her son Jamal. The computer shows an almost identical blood and tissue match between Roberto-Jamal and Jasmin-Molly. Hospital teams in both cities coordinate the “swap.” Jamal and Molly are scheduled for living donor surgery at the same time, each at the hospital nearby. When the surgery date arrives, the transplanted kidneys are rushed to the airport and flown to the corresponding city while Roberto and Jasmin are prepped for surgery. Within hours, the kidneys arrive and are successfully transplanted – Roberto with Jamal’s kidney, and Jasmin with Molly’s – examples of the miracles of modern medicine, technology, and transport.

Donor Chains

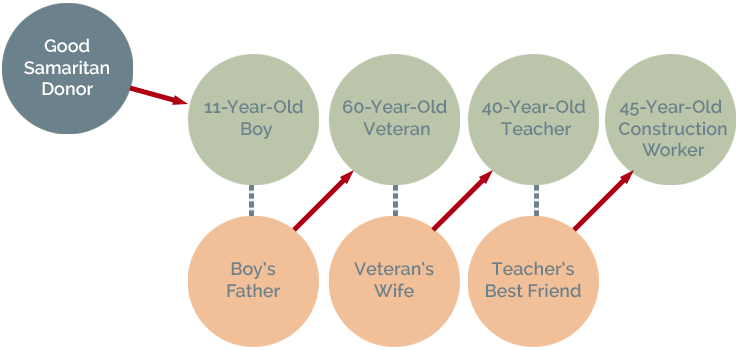

Non-directed donors can also participate in paired exchange, however it works slightly differently. A non-directed donor initiates a chain by donating a kidney to a patient who has a willing, but incompatible donor. In exchange, the patient’s would-be donor donates to another recipient. The chain continues for as long as there are recipients with incompatible donors still willing to donate. Donor chains require the use of large computer databases with algorithms that search for matched pairs. In addition, chains require considerable coordination between transplant centers in order to make them successful. The benefit comes down to lives saved. Chains often involve difficult-to-match patients who, without a paired exchange program, might linger on the waitlist for years. To date, the longest kidney chain led to 51 transplants.

Example Scenario

Jennifer, from Cincinnati, has just finished watching the film, Perfect Strangers, which documents a woman’s journey to donate a kidney. She is inspired by the story and moved by the struggles kidney patients endure on dialysis. After extensive research and soul-searching, she decides that she wants to donate a kidney anonymously. She learns about a donor chain involving 30 patients, 30 donors, and 17 hospitals in 11 states. At a local transplant center, Jennifer is screened, evaluated, and deemed a good candidate for living donation. After mentioning her interest in donor chains, her doctor enters her health information into the system. After several months of coordination between hospitals, she travels to Boston to undergo surgery. Her kidney is donated to an 11-year old boy whose father donates to a 60-year-old army veteran in Boston. In turn, the vet’s wife donates to a 40-year-old school teacher in New York city, whose best friend donates to construction worker in Buffalo. After two days in the hospital, Jennifer returns home glowing at the thought of having saved four lives.