by Josh Morrison | Aug 22, 2016 | Uncategorized

Back in June, I, like so many Americans, was shocked and horrified at the awful tragedy at Pulse Nightclub in Orlando. So many innocent lives lost in the latest mass shooting in the United States! A massacre so devastating, that it has brought together those who previously disagreed on the nations’ gun laws. A step in the right direction!

As I pondered the loss of innocent lives and prayed for the families affected by the carnage, I couldn’t help but think of the kidney patients who die every day waiting for transplants. The number of people killed in Orlando would be similar to the number of kidney patients dying every 2 to 3 days. Isn’t it shocking!

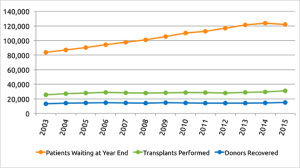

The truth is, the gap between those on the waiting lists and the number of transplants performed annually in the United States keeps growing by the thousands. For the past 5 years the number of transplants have remained flat and the need multiplies. I wonder who is noticing these figures and finding solutions to this problem. Is there a shortage of kidneys? The answer is a simple NO!

Let me share a recent story. To protect the subject’s privacy, we will call this “Miriam’s story”. Miriam is a senior citizen who has recently retired. Over six months ago, I was approached by her daughter to help Miriam get a kidney transplant. However, there was no further contact until Miriam was in emergency and was admitted to receive dialysis in the hospital. Miriam was in serious condition and was in the hospital for several days. After her release from the hospital Miriam went for dialysis at the local dialysis center. I felt it was strange that Miriam had not been dialyzed earlier at the dialysis center.

On further inquiry, I was informed by Miriam’s daughter, that her nephrologist had told her, “if she started dialysis it would hurt her chances of receiving a kidney transplant”. This wasn’t the first time I had heard this sort of precautionary tale. It was time to check with those who should know about these things. When I inquired I was informed, “this is not true and further education needs to be provided for the nephrologist through the local CMS network”. Lesson learned – double check and get a second opinion or you may find yourself in the emergency room of a hospital.

Miriam had received a fistula several months before she went into the dialysis center. Therefore, she was ready to receive dialysis through a fistula. This was good news. However, she was in severe pain when the needles were inserted. After, speaking with Miriam’s daughter regarding using Lidocaine, I was informed that the dialysis center would not give Miriam Lidocaine shots. After speaking with the Administrator of the dialysis center, I was told the manager would not allow these shots for Miriam. Having been in dialysis for 50 months, where I received Lidocaine shots every time, I find it strange the same cannot be given to Miriam.

Now came the time to find living donors for Miriam. I was pleased to learn 5 extended family members had applied to be donors for Miriam. However, during the past 6 months no progress had been made to test the potential donors. It was time to speak with the living donor coordinator. After explaining my story and the work Living Donor Outreach does in educating the transplantation community to increase donors, the coordinator agreed to speed up the process. Lesson learned – must stay on top and don’t wait for things to happen by themselves!

True to her word, the coordinator sped up the process and rejected all five donors within a month! Shocking one would say! She rejected the potential donors on the basis of family history of diabetes! None of them had diabetes. We asked for a copy of the protocol from the institution. We were provided a slide presentation, which did not reject donors because of a family history of diabetes. They were not following their own protocol. Lesson learned – beware of cherry pickers! They will let you die!

We could have fought the decision, but we thought it better to contact other centers around the country and locally to get a second opinion. Other living donor coordinators told us they would not reject a living donor because of family history of diabetes but will test the candidates and possibly have some extra tests. Lesson learned – get a second opinion! It may save your life!

Here’s the irony! The center that rejected the potential donors, requested my program, “Proactive Education for Family & Friends” to train their medical students 9 months ago. hopefully to increase living donors.

Today, Miriam’s health records have been sent to the new transplant center and we have been told everything is on track. They will contact us if they need any further information. Lesson learned – Don’t give up!

This is just one recent case, among many, of ESRD patients finding it difficult to maneuver through the system to receive a transplant. After extensive research, we have found a lack of education, at all levels, is a major problem afflicting the transplantation community to increase donors. Although Miriam’s daughter and other members are in the medical field they found it difficult to do the right thing for their mother. They said, “Thanks for helping us, we were lost!”

by Josh Morrison | May 3, 2016 | Uncategorized

About four years ago, I donated my kidney to someone I didn’t know. Today I work in the transplant field for a living, so being a donor comes up a lot. It’s basically the first thing most people find out about me.

Which I really hate, to be honest: I don’t like seeming different, like people assume I’m some sort of saint. That’s not how I see myself. It’s not how I want others to see me.

On top of that, every time someone asks me why I donated (which is always), I never really know what to say.

It’s not that I lack for explanations. I’ve dissected my decision to death. The explanations I give tend towards the clinical—causal factors explicating my aberrant behavior. I’d had anesthesia before; I overemphasize abstract reasoning and principles; I went to Catholic school; I have a savior complex, etc.

That doesn’t include the jokes I tell because explaining makes me nervous: “I was a corporate lawyer and wanted the time off.”

But that just list traits like I’m talking about someone other than myself. Mix that with the humor, and it’s just a way to pretend I’m in the same spot as my interrogator: “I know it’s weird too.”

That hides the way I really feel about it, hides my earnestness. I gave because if I didn’t someone would die. None of my other reasons matter.

It didn’t need to be my responsibility. No one’s ever obligated to be a kidney donor, to anyone, for any reason. I chose to take that on myself.

For most donors, giving a kidney fulfills a need closer to home – saving the life of someone they care about. But there too, I think an essential step is to assume a responsibility that you have every right to walk away from—choosing to voluntarily burden yourself with the needs of another; choosing to answer that need by sacrificing of your own body.

We live in a transactional culture where we’re told always to put yourself first. Don’t take on burdens that aren’t yours. No one’s entitled to your help. Look out for number one.

That makes discussions about giving an organ really difficult. It feels like people often take living donation as an indictment of their own choices—if you don’t know whether you’d give a piece of yourself to save a friend’s life, does that make you a bad person?

Of course not. No one needs to take on obligations that aren’t theirs. But, for me, the choice to accept responsibility enlarged my own life, made it richer with purpose. Becoming a kidney donor was the best decision I ever made. It made me happier than anything else I’ve done in my life.

I’d wanted to donate for years. When I finally did, it felt like running my first half-marathon or graduating from law school. It was an achievement I’d deliberately planned and had to work to make happen, like summiting my personal Mt. Everest. I had gotten the chance to live out the best version of myself.

For many people, donation only deepens their sense of self—confirms the potential they knew they had all along. Many see it in practical terms: when someone I cared about was in need, I merely answered the call. They go back to their lives feeling joyous but largely unchanged.

That’s not what it was like for me. The experience turned out to be addictive. I had been working in a job that meant nothing to me besides the paycheck. Suddenly I felt drawn to a higher calling, though I didn’t yet know that meant working to end the transplant shortage. When I donated, I had set my mind and accomplished something profound. Now that I knew I had that power, I couldn’t just go back to the compromises I’d been making.

The road to where I’ve ended up was a long one. I tried to be a writer and failed at it. I left my home and the woman I lived with to start a new career in Toledo, Ohio. (I didn’t know anyone within two hundred miles). I received a grant, came back to the east coast, and started Waitlist Zero.

Ending the kidney shortage is my life. It wasn’t when I donated, but the same feelings that made me a donor then make me want to find everyone a donor now. The same things that make me uncomfortable telling my story as a donor keep me from speaking on my passion for Waitlist Zero.

Waitlist Zero means finding a transplant for everyone who needs one. It means that access to medical care shouldn’t be contingent on your skin color or your health insurance or how many friends you happen to have or how healthy they happen to be. It means that no one should ever have to feel the loneliness of wondering if anyone cares about you enough to save your life. It means tens of thousands of families each year shouldn’t have to go to someone’s funeral and wonder if they could have done more.

I wish I could say that this passion for ending the shortage was broadly shared but it’s not—for the simple reason that most people in the field don’t believe it’s even possible. Doctors are passionate about caring for their patients—incredibly passionate. But for decades the shortage has been growing and growing and the number of transplants has just stayed the same.

It gets tiring to hit your head against the same wall; after a while you forget that anything better exists. It’s hard to expect faith in the possibility for change.

But I do have that faith. It’s what sustains me through the travails of starting a new business and feeling sometimes like I’m making every possible mistake along the way. And I could give a dozen reasons why ending the shortage is possible: how living donation saves the government hundreds of thousands of dollars per patient; how studies show educating patients and their families can nearly double the rate of living donation; how if only one in ten thousand Americans donated each year, there’d no longer be a shortage.

Right now, six in seven people who need a transplant can’t find a living donor—I refuse to accept that six in seven Americans don’t have someone able and willing to save their life if only our community did a better job of supporting donation.

Yet those are just rational reasons. Ending the shortage is a transformational change: something more is needed than mere logical deduction. Otherwise it would have happened already.

What drives me to keep going is less rational certainty than the conviction that the field needs at least one person who believes the shortage can be defeated—the hundred thousand patients on the waiting list deserve champions who refuse to accept their deaths as inevitable. And we deserve a community where people take responsibility when they don’t strictly have to, a community that supports transplant and never lets die somebody who only needs a willing donor to live.

.

by Josh Morrison | Jan 14, 2016 | blog

Josh Morrison is a kidney donor and the Executive Director of Waitlist Zero

Waitlist Zero opened our doors a year ago with the mission of supporting living donors and living donation. It was founded by two kidney donors: myself and Thomas Kelly. Before then, no group represented kidney donors first and foremost. And believe me, it showed.

It’s been thirty years since the National Organ Transplant Act was passed, sixty years since the first living donation. But donors still lose wages to donate kidneys. We still have no guaranteed health insurance, still receive no follow-up care after the first twenty-four months. The donation experience at far too many hospitals is confusing and inconvenient: too often being a donor requires an act of will just to fight through the bureaucracy. We deserve better.

But, honestly, if this were only about how kidney donors are treated, I would never have started Waitlist Zero. Like most donors (more than 95%!), donation is a decision I’d make again. I knew the system was imperfect; I knew there were risks. But what motivated me was saving the life of the person I gave to.

Patients with kidney failure are the real victims of our dysfunctional system. The numbers alone are staggering: 100,000 patients on the waitlist; as many as 80,000 more patients who could use a transplant but aren’t listed; a shortage of 20,000 transplants each year; six out of seven waitlisted patients unable to find a living donor.

But what matters more are the lives and families affected. On a Facebook support group this weekend, I saw a man post about his husband who died on dialysis. He loved his life. Together they traveled to 16 countries in 18 years, and adopted many pets. I don’t know if he could have used a transplant, but so many people could.

As a donor, I know my recipient, John, will likely need another kidney. And before he does, we need to build a transplant system that doesn’t take deadly shortages as a given: one of transplant support that makes transplants easy to ask for and easy to give.

That’s why the interests of donors and recipients are inextricably linked. In our first year, we focused our advocacy efforts primarily on increasing living donation. We brought together a Coalition of sixteen member organizations united by our goal of promoting living donation. We signed up nearly five hundred kidney donors to our letter in support of better transplant policy. We brought together the most important groups in the field to meet with the federal government and persuade them to open up $9M worth of grants to living donation.

We are proud of our first steps as an organization, but in 2016 we want to broaden our focus and connect more fully with the donor community. Last year, we asked more than 180 donors about their experiences because we want to hear what you had to say. Our new Project Director, Steve Rice, went through all these responses and pulled out the common themes. He did a great job, and after the holiday we’re going to publish his piece about what donors are telling us about their transplants.

We’re also going to start featuring kidney donor stories. Starting next week, we’ll launch the donor portrait series. You’ll see a blog post a day, each featuring the story of a living kidney donor. Taken together, the portrait series will frame the diversity of motivations, journeys, and post-donation reflections of donors. By the end, we’ll host each story on the Donor Stories section of our website.

But this is just the beginning. We need to make the voice of kidney donors heard in the transplant field. To do that we need your help. If you’re a kidney donor, we need your passion and your advice, your criticism and your support. We need to help the transplant field hear everything you have to say.

If you’re not a donor, we need you too. We need recipients; we need families; we need patients on dialysis. We need everyone who wants to do something, however small, to save a life.

If you want to fight to support living donors and living donation, sign up here. We need you.

Recent Comments