by Stephen Rice | Apr 5, 2016 | Uncategorized

Eight years ago, Josh Morrison was in law school and doing what one often does while in school – reading. While most of his time was spent reading case law, in the fall of 2007 he happened to come across an article about a woman who needed a kidney. He was struck by the safety of the procedure and the fact that one could save a life without much impact on his or her own health. More than that, he was struck by the plight of the woman. She’d had three possible donors, but all three backed out. He empathized with the thought of being in that situation – having to test out whether his friends or family liked him enough to give one of their organs. He imagined what it would be like to have to beg for his own life.

He didn’t act, but the article had planted a seed.

A year passed and Josh found himself staring at another article on the subject. This time it was about a Good Samaritan donor. He decided that he wanted to do it. He did his research, but his wife at the time was very uncomfortable with it. When they divorced for other reasons two years later, he was able to pick up the list of things he wanted to do. Donating a kidney anonymously rose to the top.

Josh’s hope was that he would be able to initiate a donor chain. It looked as if he’d be able to start a chain of five-to-six donations. “It fell through. The hospital only did chains once a month, and I didn’t have the ability to take more time off of work so I donated to the next person on the list,” said Josh.

That ‘next person’ happened to be J.D. Mendes, also from Boston. J.D.’s kidney failure had come out of the blue. He didn’t know that he had kidney disease until one day he collapsed. He was in so much pain that he thought he was dying. JD spent the next eight years on dialysis – eight years waiting for a new organ to become available.

Four months after their surgeries, Josh and J.D. were able to meet. The meeting took place at the transplant center. Several social workers were present, plus JD’s mom. “It was very emotional,” recalls Josh. “He’s an eloquent and charismatic story teller and he told me his story. It was one of the most profound experiences of my life.”

Asked to reflect on the experience, Josh said, “the most satisfying part was the experience of achieving something great that I could have given up on, but didn’t. I felt like other achievements would be possible.” Josh feels that many times, others don’t understand his motivations. “There’s nothing better about me than anyone else. I think I’m pretty normal, but others’ reactions can make me feel very different sometimes,” explains Josh.

Josh’s advice for patients and potential donors is both practical and insightful. On the practical end, Josh recommends using an abdominal binder during recovery. “Don’t lift a lot of weight because you’ll get a hernia. And have some food frozen in the house.” Josh adds, “For those considering becoming a Good Samaritan donor, think about starting a chain.”

Josh’s more insightful advice is for patients. “I once spoke to a person on dialysis who described to me the many funerals she’d attended for people who’d also been on dialysis, but who didn’t seek out a transplant. It must be a horrible feeling for family members to think ‘I could have done more.’ Please talk to family members about it. It’s not just the patient who benefits. It’s the whole family.”

by Stephen Rice | Mar 30, 2016 | blog

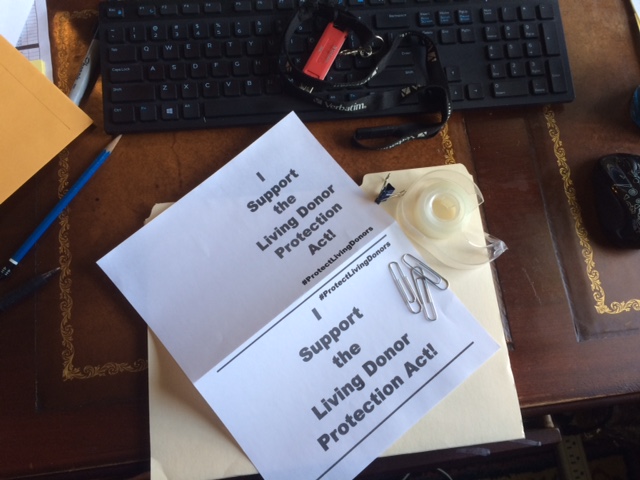

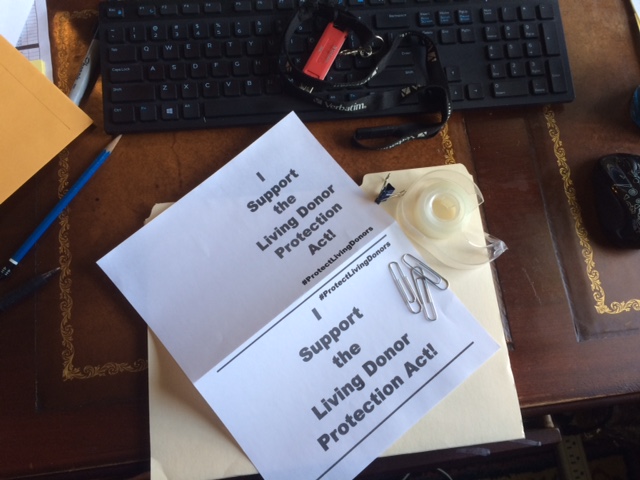

No one should expect to be worse off for having donated a kidney

Important federal legislation has just been introduced in Washington DC. The Living Donor Protection Act aims to prevent insurers from discriminating against kidney donors and guarantees that all donors are protected by the Family Medical Leave Act. It is an urgent priority across the kidney transplant field, and a much-needed first step for the transplant support agenda.

Throughout April – National Donate Life Month – WaitList Zero will be promoting awareness of the Living Donor Protection Act and encouraging living donors; transplant recipients; and their networks of family, friends, co-workers, and community members to urge their members of Congress to support passage of this critical legislation.

Here’s how you can help:

- Please ask your federal legislators to support his Act by using an online app located here. Every message helps. It takes two minutes, but it will make a big difference. If you have time to customize it with your story and why you’re passionate about transplant, even better!

- Take the Selfie Challenge!

What is the Selfie Challenge?

Once you’ve contacted your legislator using our online app, the next way you can help is by taking the Selfie Challenge. The Selfie Challenge is a social media campaign to spread awareness about the Living Donor Protection Act – in about 5 minutes.

The people in your network love seeing your face. They really do! In a nutshell, we’re asking you to take a selfie (using the instructions below), and post it to your Facebook page to encourage your Facebook friends to use the online app to contact their legislator. Remember, using the app only takes a couple of minutes and they are done! Good deed for the day – check √.

Here’s what you do:

Step 1 — Find some supplies to make a sign that reads I Support the Living Donor Protection Act, or print out a sign located here.

and I’ll repost for you.

Step 3 — Post your Selfie to your Facebook page with the following message (or something similar).

Step 3 — Post your Selfie to your Facebook page with the following message (or something similar).

“I’m participating in the Selfie Challenge to support the Living Donor Protection Act because after living kidney donors give the gift of life, it’s the least we can do to make sure they’re treated fairly. You can help me to support this campaign by going to the online app to send a message to your federal legislator. Every message helps. It only takes two minutes, and it will make a big difference.”

Step 4 — Sit back and feel good about helping to protect living donors against discrimination.

by Stephen Rice | Mar 24, 2016 | blog

In 1984, David Reid was settling into married life with his new wife Maggie. She hadn’t been feeling herself including some trouble sleeping and decided to visit her physician, who found that her blood pressure was extremely high. Tests revealed a form of Lupus, which had attacked her kidneys and already reduced their function severely. She was given a massive dose of steroids which saved her kidneys, but the episode left her with only 25% of normal function. “It was a devastating blow,” said David. “It totally changed our lives.”

Over the next 20 years, Maggie, with David’s support, would manage the health effects of Lupus and reduced kidney function. However, things deteriorated over time and by 2005, her kidney function was almost gone. It was time for them to make a decision. “We knew enough about dialysis to know that it was a debilitating condition with serious health problems. It seemed like life was over. We needed to figure out what to do,” remembers David.

Fortunately, David was a universal donor (blood type O) and Maggie was a universal recipient (AB positive), which made him a potential candidate for living donation. He was tested and realized that he could be his wife’s donor. “It was a solution that we had right in the family.”

David began the intensive health screening to ensure that a future donation wouldn’t be putting his own life – or Maggie’s in harm’s way. The tests would determine whether he was healthy enough to be his wife’s donor. “It was a very careful process and nerve-wracking. I desperately wanted to be her donor.”

David qualified and they prepared for the solution to a problem that had impacted their entire family. Asked how he was feeling right before surgery, David commented, “It was exciting. After 20 years of Maggie’s declining health, it was the big day. I felt like I was creating a solution for her.”

Post-surgery was difficult for Maggie. David remembers that she was in rocky shape the first few days after surgery including having some difficulty breathing, but her team of doctors and nurses solved the problem. His surgery was smooth, but he notes that he had some pain and it took one or two days after his catheter was removed for his remaining kidney to begin producing normal urine flow. His medical team assured him this was to be expected due to the recovery process and the effects of pain medication.

Maggie and David had lived with her disease during their entire marriage, but the transplant had made a huge turn-around in her health. Because her Lupus was centered on her kidneys, her transplant essentially cured her of the disease. David says, “All of her Lupus symptoms were gone. The new kidney was a magic bullet. It saved her. She went from being chronically ill to being healthy. We’d never really known what that was like.”

David’s advice to a person considering donating a kidney to a spouse is to ensure that they have enough support available during recovery. At the time of transplant, they had children ages 4 and 7. “Make sure it’s manageable,” advises David. He adds, “If you can do it, do it. It’s not that difficult to do. The surgery is routine and my recovery was quick. The feeling of allowing someone else to live is hard to describe. It’s a feeling that will be with me my whole life. Whatever else happens, I’ll always know I’ve done something truly good in the world.”

by Stephen Rice | Mar 23, 2016 | blog

WaitList Zero occasionally publishes guest blog posts written by members of our community in the hopes of sharing viewpoints from various perspectives.

The Benevolence Boomerang

By Eldonna Edwards

Ten thousand thoughts are not as good as one action. ~~Adyashanti

From as far back as I remember I’d always associated the word philanthropy with wealthy individuals or organizations who donate money to charitable causes. People like Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, Ted Turner, and rich widows who leave lofty estates to libraries or colleges. What I’ve come to learn is that the Greek etymological root of philanthropia is “love of mankind.” Philanthropy is simply being of service to one another through concern for the welfare of our fellow human beings.

back as I remember I’d always associated the word philanthropy with wealthy individuals or organizations who donate money to charitable causes. People like Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, Ted Turner, and rich widows who leave lofty estates to libraries or colleges. What I’ve come to learn is that the Greek etymological root of philanthropia is “love of mankind.” Philanthropy is simply being of service to one another through concern for the welfare of our fellow human beings.

I am not a rich woman, nor did I grow up privileged. However, as the daughter of an evangelical minister I learned from a very young age that no matter how poor you we

re, giving back was imperative. I no longer attend church or subscribe to any religious denomination. I tend to describe myself as a devout agnostic, meaning I’m sincerely uncertain about a higher power or what happens after we die. But, what I am fairly certain about is what matters before we die. It is my belief that each one of us can make a difference in the quality of other human lives. Whether that means going the extra mile for one’s patient, giving money to a reputable charity, offering your time at the women’s shelter, or, in my case–donating a kidney to a stranger on dialysis–each is a path toward the same goal. Every interaction with a single individual creates an opportunity to alter both of your lives for the better.

Altruism is defined as the principal of practice of unselfish concern or devotion to the welfare of others. It exists in order that we take responsibility for the greater good of our human community and to create balance for the inequality and unconscionable inhumanity that persists in the world. I take issue with the word “unselfish” because I can tell you from experience that when you help someone it feels good. I prefer to call it enlightened self-interest. There is no metric for calculating the outcome of donating your cans and bottles to a needy family collecting returnables or paying for the person ahead of you in line at the grocery store but the immediate reward—that rosy feeling we get when contributing to the greater good—makes us happy, and thereby motivates us to continue the cycle of giving.

The question I’m most asked is, “Why? Why would a healthy individual put herself at risk, give up an organ to someone she doesn’t even know? Why go so far out of my way to donate a kidney when this disease hasn’t affected a close friend or anyone in my immediate family? Why not just donate my time instead of one of my vital organs to someone I don’t even know?”

These are all perfectly legitimate questions however, my motivation wasn’t born out of logic so it’s difficult to explain. But I’ll try. When I was eight years old a new family moved into our small rural town. The father dug wells for a living and their ramshackle home housed half a dozen kids. Two of the girls ended up in my second-grade classroom and both showed up wearing the same clothes to school every single day. When I asked one of the siblings why she never wore a dress she answered that she didn’t own one. Our family didn’t have much and most of my clothes were hand-me-downs from my older sisters but I knew my two new classmates had less than I did. Way less. The next day I selected two dresses from my closet and gave them to the girls. You would have thought I’d given them tickets to Disneyland based upon their reaction. It is my first memory of the correlation between donor and beneficiary and I’ve never forgotten it. Forty years later I met a woman with kidney disease. I had two so I offered to give her one of mine. She turned me down, partly because she wasn’t ready and partly because at that time, non-related donors weren’t accepted at most transplant hospitals. Little did she know that our chance meeting set me on a path I never expected and that the gifts I’ve received as a result are much greater than the one I’d offered.

I truly believe we are all brothers and sisters in this world and that by helping one person you help the collective. I believe each of our deeds, good or bad, creates a ripple. Birth might be about circumstance but  life is about choices within the events that occur year to year, day to day, and most importantly, moment to moment. What looks random in the immediate moment might seem like fate for those that believe in predestination. For me, it was merely an encounter with a person with kidney disease who raised my consciousness about a particular form of suffering and I chose to act upon it. Knowing my donation made a positive difference in the life of a recipient and his loved ones is awesome. And even better, if sharing my donation story helps just one more person consider living or deceased organ donation then everything will have been worth it.

life is about choices within the events that occur year to year, day to day, and most importantly, moment to moment. What looks random in the immediate moment might seem like fate for those that believe in predestination. For me, it was merely an encounter with a person with kidney disease who raised my consciousness about a particular form of suffering and I chose to act upon it. Knowing my donation made a positive difference in the life of a recipient and his loved ones is awesome. And even better, if sharing my donation story helps just one more person consider living or deceased organ donation then everything will have been worth it.

Between A and B, life and death, all we have is each other and I believe our purpose is to be of service, make a positive contribution to the world, relieve suffering and bring joy to others. To that end, I’m grateful for each person with kidney disease who has touched my life with stories of hardship and hope. And I’m thankful to all the doctors, nurses and other important fibers of the amazing tapestry of medical miracles in the dialysis and transplant field for not only giving sick people a better quality of life but for helping people like me find deeper meaning and a higher purpose in life. It is an honor to be one of the tiny threads woven into our overlapping lives.

Eldonna Edwards is the author Lost in Transplantation: Memoir of an Unconventional Organ Donor. Her story chronicles a life-changing decision to donate a kidney to an ailing stranger. Eldonna is also the subject of the film “Perfect Strangers” an award-winning documentary following one kidney patient and one potential donor in their search for a possible match. Eldonna is a Donate Life Ambassador and a donor-mentor with The American Transplant Foundation. She is available for inspirational keynote and/or educational breakout sessions at your meeting or conference. Follow her on Facebook or Twitter. Her debut novel is planned for publication in the near future.

by Stephen Rice | Mar 17, 2016 | blog

President’s address to the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS)

Excerpt

Winter Symposium, January 14, 2016

Charles M. Miller, President

(Full speech is available for viewing at http://asts.org/education/events-meetings/winter-symposium/previous-winter-symposia)

Beauty and the Beast

Part 1 of 2

Introduction

First, I want to say that the last 8 months as President of ASTS have been an absolutely incredible experience. It’s been a terrific opportunity and honor. To say I’ve learned a lot from colleagues and ASTS staff would be an understatement. While very busy and sometimes challenging, mostly it has been a joy having the bully pulpit and representing this great Society in discussions and conversations with colleagues, thought leaders, policy makers, regulators, and allied organizations.

For organizations like ours, the million-dollar question is always – as a field and as a community, where are we and where do we want to go? The theme of the last few days says much of it – “Limited Supply, Increasing Demand: Expanding Organ Donation.” I know – it’s the age-old question in transplantation. But it remains at the epicenter of the many challenges we face as transplant surgeons.

Resource scarcity is our special burden as transplant specialists. It is truly the issue that differentiates transplantation from all other medical specialties and is the issue I focused on for both the theme for the Winter Symposium as well as the theme for my Presidency.

Working with this wonderful group made me think back in time to a place very early in my career when I was full of energy, enthusiasm and the desire to be innovative and look for a field in surgery that would allow my imagination to soar. And today, I have 2 stories to tell you. I call them collectively, “Beauty and the Beast”.

The Beauty

The first story, which I call “the Beauty,” took place relatively early in my residency. [I had been] invited me to spend my entire 3rd year of residency working on the transplant service in both a clinical and bench-top research capacity; it was an incredible opportunity. The combination of clinical and bench work was the epitome of translational education and clinched my interest and passion in transplant.

The first story, which I call “the Beauty,” took place relatively early in my residency. [I had been] invited me to spend my entire 3rd year of residency working on the transplant service in both a clinical and bench-top research capacity; it was an incredible opportunity. The combination of clinical and bench work was the epitome of translational education and clinched my interest and passion in transplant.

My bench research was investigating the combination of donor specific blood transfusions and Cyclosporine in the rat heart transplant model. My problem was mastering the heterotopic heart transplant; I think I killed most of the rats in NY! The problem was that every time I thought I was getting the hang of it, my beeper went off with an urgent clinical issue that took precedence; it was really challenging. I had just starting dating someone new a few months earlier and I had the bright idea of a really cool date; we could both go to the lab one evening. There would be peace and quiet; I might get the “interruption free zone” I needed and she could see what I was doing or more likely just read her book. What a cool guy I was… anyway she agreed!

I got through the procedure and got ready to release the clamps with a dread based on my passed 100 failures. But I took the clamps off, there was no bleeding and the heart started to beat for the first time. I let out a shriek of joy and called in my girlfriend Erica to see. She was amazed. It was a magical and exhilarating moment that we shared and fully enjoyed.

I think her support that night gave us both an enduring passion for the field and the mutual commitment to endure through the many hurdles that might come in the years ahead. And I discovered that with commitment and persistence, I could perform these heart transplants with a high rate of success that ultimately allowed for a publication in Transplantation. More importantly, I think I found my career and my wife that night!

The Beast

So now for the “Beast.” After a time working and living in Pittsburgh, I returned to New York in 1986 to start-up a liver program at Mt. Sinai Hospital only to find enumerable state and local political hurdles. [But] after 18 long months, we got the necessary approvals and our young team was rarrin’ to go!

So now for the “Beast.” After a time working and living in Pittsburgh, I returned to New York in 1986 to start-up a liver program at Mt. Sinai Hospital only to find enumerable state and local political hurdles. [But] after 18 long months, we got the necessary approvals and our young team was rarrin’ to go!

The first case was a resounding success. Lots of high fives! The second case, not so good. The liver graft didn’t function, but followed by successful re-transplant. Then our third case – another bad graft! A beautiful 18-year-old girl with severe autoimmune hepatitis. High enzymes, coagulopathy, but this time a positive cross-match. Having seen one case of hyperacute rejection in Pittsburgh, and feeling rather desperate not to re-transplant 2 of our first 3 cases, I decided on a course of immune therapy. I put on my rose colored glasses and tried to convince myself daily that things were improving…until she crashed, was resuscitated, re-transplanted too late, and died a week later of sepsis.

In that moment I saw the terrible conflict I was confronting. [On one hand,] my physicians’ duty to the patient and [on the other, my] fiduciary duty to the institution to have a program with great results that wasn’t wasting organs. But the truth was I hadn’t had the fortitude to do the courageous thing of putting my patient’s best interest first, re-transplanting her early and accepting another early graft loss. I had tried to satisfy both interests and failed miserably. It was crushing and I found myself in a back stairway crying my eyes out and re-thinking everything. I was furious with myself, scared and feeling quite alone. But stairwells get used by others and a senior surgeon came upon me and kindly spent some time listening. I actually don’t remember the substance of the conversation, but I do remember the message – just collect your thoughts, re-focus and keep moving forward, and always try to put patients first.

Thirty years later, this “Beast” of transplantation continues to haunt everything we do. So I ask you today – how can we stay true to our collective vision of “saving and improving lives with transplantation” and do the best for all of our patient’s in a scarce resource, highly regulated “battlefield triage” environment? How do we transform the Beast into the handsome Prince that Beauty eventually marries?

Strategic Plan

There are no simple answers, but I believe the root cause that differentiates us and creates so many of our problems, regulations and tribulations is organ scarcity. So what can we do?

I dream of practicing transplant surgery in a non-scarce resource environment, but this dream is no small goal. “The Beast” survives and thrives because we must deal with the complex pressures and burdens that scarce resources impart. But the goal, if achieved, has the potential to change the way we think about and practice transplantation. To address the issue of organ scarcity in a transformative fashion will take a highly coordinated approach that encompasses each of the four sectors of the ASTS strategic plan – optimal patient care, advocacy, research, and training and professional development.

I dream of practicing transplant surgery in a non-scarce resource environment, but this dream is no small goal. “The Beast” survives and thrives because we must deal with the complex pressures and burdens that scarce resources impart. But the goal, if achieved, has the potential to change the way we think about and practice transplantation. To address the issue of organ scarcity in a transformative fashion will take a highly coordinated approach that encompasses each of the four sectors of the ASTS strategic plan – optimal patient care, advocacy, research, and training and professional development.

Optimal Patient Care. In June, I asked Dorry Segev to lead a new task force to review issues in organ donation and access, understand the myriad of initiatives already underway, and create a Society white paper that will then inform a 5-year strategic plan on this issue. For example, the National Living Donor Assistance Center (NLDAC) is an important piece of our Optimal Patient Care strategy by helping donors avoid financial disincentives. NLDAC program has helped 2,500 recipients since it began, and saved Medicare over $60 million in dialysis costs. Most importantly, almost 75% of donors who have participated in NLDAC say they wouldn’t have been able to donate without it.

Advocacy. As I toured the country this Fall to attend UNOS Regional Meetings, the sense of PSR and CMS induced risk-aversion in candidate and organ selection was on the top of everyone’s mind. We all know what happens with flagging and the potential for SIA’s. Risk aversion flourishes; needy and deserving, but more risky patients without “good risk adjusters” go unlisted; and 4,000 organs that are procured get discarded. Program preservation begins to overtake and supersede patient care.

Through careful planning and intense diplomatic discussions with the UNOS Board, a resolution was passed that instructs the MPSC to create a group of quality metrics that are able to identify programs with only clinically relevant quality issues; and to create this plan in the next 6 months! These changes have the potential to create a climate that incentivizes the type of calculated risk-taking that promotes organ donation and utilization and improves overall patient care. We must keep the pedal to the metal so as not to lose momentum!

Research. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) study on organ donor intervention serves as a tangible example of ASTS’s tenacity. In a move of leadership, ASTS was the first organization to publicly announce a funding commitment to the study. Since then, at least six additional groups have announced support. I look forward to the deliberations of the IOM and am confident that the recommendations that emerge will provide an organizational framework and roadmap that will catalyze more coordinated research that will lead to improved quality and quantity of deceased donor organs. There is light at the end of the tunnel!

Training and Professional Development. Meetings such as the Fellows’ Symposium, ATC, the new “lap” donor course and the Winter Symposium exemplify how ASTS uses training and education to support [big goal achievement]. I am very excited to remind you that you are in for a compelling session this afternoon with our 6 former Surgeons General. [Former Surgeon General Ken Moritsugu has suggested the idea of a] national campaign to increase organ donation; a campaign with the imprimatur of the Surgeon’s General office, along the lines of the campaign to reduce smoking. I am sure what will start today will raise societal awareness of this growing public health issue and strengthen our resolve to galvanize the community around our goal and our vision to save and improve more lives through transplantation.

–to be continued–

Step 3 — Post your Selfie to your Facebook page with the following message (or something similar).

Step 3 — Post your Selfie to your Facebook page with the following message (or something similar).

back as I remember I’d always associated the word philanthropy with wealthy individuals or organizations who donate money to charitable causes. People like Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, Ted Turner, and rich widows who leave lofty estates to libraries or colleges. What I’ve come to learn is that the Greek etymological root of philanthropia is “love of mankind.” Philanthropy is simply being of service to one another through concern for the welfare of our fellow human beings.

back as I remember I’d always associated the word philanthropy with wealthy individuals or organizations who donate money to charitable causes. People like Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, Ted Turner, and rich widows who leave lofty estates to libraries or colleges. What I’ve come to learn is that the Greek etymological root of philanthropia is “love of mankind.” Philanthropy is simply being of service to one another through concern for the welfare of our fellow human beings. life is about choices within the events that occur year to year, day to day, and most importantly, moment to moment. What looks random in the immediate moment might seem like fate for those that believe in predestination. For me, it was merely an encounter with a person with kidney disease who raised my consciousness about a particular form of suffering and I chose to act upon it. Knowing my donation made a positive difference in the life of a recipient and his loved ones is awesome. And even better, if sharing my donation story helps just one more person consider living or deceased organ donation then everything will have been worth it.

life is about choices within the events that occur year to year, day to day, and most importantly, moment to moment. What looks random in the immediate moment might seem like fate for those that believe in predestination. For me, it was merely an encounter with a person with kidney disease who raised my consciousness about a particular form of suffering and I chose to act upon it. Knowing my donation made a positive difference in the life of a recipient and his loved ones is awesome. And even better, if sharing my donation story helps just one more person consider living or deceased organ donation then everything will have been worth it.

The first story, which I call “the Beauty,” took place relatively early in my residency. [I had been] invited me to spend my entire 3rd year of residency working on the transplant service in both a clinical and bench-top research capacity; it was an incredible opportunity. The combination of clinical and bench work was the epitome of translational education and clinched my interest and passion in transplant.

The first story, which I call “the Beauty,” took place relatively early in my residency. [I had been] invited me to spend my entire 3rd year of residency working on the transplant service in both a clinical and bench-top research capacity; it was an incredible opportunity. The combination of clinical and bench work was the epitome of translational education and clinched my interest and passion in transplant. So now for the “Beast.” After a time working and living in Pittsburgh, I returned to New York in 1986 to start-up a liver program at Mt. Sinai Hospital only to find enumerable state and local political hurdles. [But] after 18 long months, we got the necessary approvals and our young team was rarrin’ to go!

So now for the “Beast.” After a time working and living in Pittsburgh, I returned to New York in 1986 to start-up a liver program at Mt. Sinai Hospital only to find enumerable state and local political hurdles. [But] after 18 long months, we got the necessary approvals and our young team was rarrin’ to go! I dream of practicing transplant surgery in a non-scarce resource environment, but this dream is no small goal. “The Beast” survives and thrives because we must deal with the complex pressures and burdens that scarce resources impart. But the goal, if achieved, has the potential to change the way we think about and practice transplantation. To address the issue of organ scarcity in a transformative fashion will take a highly coordinated approach that encompasses each of the four sectors of the ASTS strategic plan – optimal patient care, advocacy, research, and training and professional development.

I dream of practicing transplant surgery in a non-scarce resource environment, but this dream is no small goal. “The Beast” survives and thrives because we must deal with the complex pressures and burdens that scarce resources impart. But the goal, if achieved, has the potential to change the way we think about and practice transplantation. To address the issue of organ scarcity in a transformative fashion will take a highly coordinated approach that encompasses each of the four sectors of the ASTS strategic plan – optimal patient care, advocacy, research, and training and professional development.

Recent Comments