by Stephen Rice | Mar 17, 2016 | blog

President’s address to the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS)

Winter Symposium, January 14, 2016.

Excerpt

Charles M. Miller, President

Full speech is available for viewing at http://asts.org/education/events-meetings/winter-symposium/previous-winter-symposia

Beauty and the Beast

Part 2 of 2

Altruism: A Core Value in the Field of Transplantation

So those are [some] of the specific initiatives that make up this evolving strategy. But what do we use to hold this strategic initiative together; what is the glue that keeps us focused and moving in the right direction? My answer to the question is our Core Values that we live and work with. And I wanted to focus on a Core Value central to transplantation; that is altruism. It is interesting to consider that altruism is the requisite catalyst for every single transplant we do. That single fact creates a stark contrast to almost all other transactions in our media driven world where egoism, the direct opposite of altruism, seems to Trump all; sorry for the pun!

So those are [some] of the specific initiatives that make up this evolving strategy. But what do we use to hold this strategic initiative together; what is the glue that keeps us focused and moving in the right direction? My answer to the question is our Core Values that we live and work with. And I wanted to focus on a Core Value central to transplantation; that is altruism. It is interesting to consider that altruism is the requisite catalyst for every single transplant we do. That single fact creates a stark contrast to almost all other transactions in our media driven world where egoism, the direct opposite of altruism, seems to Trump all; sorry for the pun!

Most of  the transplant literature regarding altruism appropriately revolves around donors. Deceased donors, donor families and living donors alike, selflessly volunteer to make life-giving gifts to others, known or unknown, with no real identifiable benefit except the personal satisfaction of helping another. It is truly remarkable. But I want to challenge all of us to look at altruism in a much broader and simplistic way than most bioethicists and medical anthropologists commonly do.

the transplant literature regarding altruism appropriately revolves around donors. Deceased donors, donor families and living donors alike, selflessly volunteer to make life-giving gifts to others, known or unknown, with no real identifiable benefit except the personal satisfaction of helping another. It is truly remarkable. But I want to challenge all of us to look at altruism in a much broader and simplistic way than most bioethicists and medical anthropologists commonly do.

If we are to be successful, donor altruism is first and foremost, and must be recognized, respected and supported. I would argue that we need to promote the value of altruism in transplantation in a way that extends beyond purely the donors. It needs to be a Core Value that guides how we treat one another, both within the ASTS and throughout the Transplant Community. In order to truly honor our donors, we need to recognize that altruism in transplantation must be promoted and incorporated in the work we do every day and we must set an example for the providers, administrators, policy makers, regulators and the media.

There are many other simple and generous ways to express altruism. For example, we [might] better help each other with donor procurements to save each other time, effort and cost as well as avoid the well-known risk of air charters. Or, we [might] figure out more liberal ways to split livers that makes grafts easier and better to share for both your and your colleagues’ patients.

No matter how far we eventually go, altruism will remain the cornerstone of donation and transplantation, and we must incorporate that value into our professional lives as never before; we must walk the walk, as well as talk the talk.

In many denominations of religious and philosophical writings, the words “altruism” and “love” are used synonymously. And to segue back to our little fairy tale, the only thing the Beast had to learn in order to be transformed back to a Prince was to learn how to love. But can we explore pastures beyond pure altruism. What will it take to utilize positive incentives once all disincentives to donation are removed?

Well to try and answer that question, let me segue from Beauty and the Beast- altruism and love to Jim Collins’ book, [Built to Last, which focuses on] those things that successful companies have in common.

The overarching theme is the importance of Core Values. As important as a good business plan is to a company, the great and enduring companies have both a good plan and a clearly enunciated set of Core Values that guide how they work on the plan every day.

We need as a Society a well-thought-out  and clearly enunciated set of Core

and clearly enunciated set of Core

Values that guide us. Make no mistake about it, when the time comes to explore incentives beyond pure altruism there will be harsh and loud critics; some with absolute religious zeal. We cannot be defensive. We must be prepared and armed with our own set of Core Values to gain the ethical high ground. So I tell you today that I will make the discussion and promulgation of ASTS Core Values a priority for the remainder of my presidency, for they will be the fuel, the glue and the armor needed to make our Strategic Plan successful.

Collectively, we can affect change. The ASTS is a big team whose members are fully committed to improving the field. We’re trying to get it right by focusing on our Strategic Plan. And it is only through your ideas, dedication, passion, expertise and hard work that we can make real change.

When I look out from here, I see a vibrant and eager group looking to help and looking to lead; and when we work together we can really effectuate positive change for our patients and donors who always continue to inspire. And this is why today; I feel such pride – pride in our field and pride in you, our Members and friends.

And so today, I am more optimistic in our future than ever before. And through our adherence to our Strategic Plans and Core values, our work will be transformative and bring new promise to our patients and to the field.

by Stephen Rice | Mar 16, 2016 | blog

About four years ago, I donated my kidney to someone I didn’t know. Today I work in the transplant field for a living, so being a donor comes up a lot. It’s basically the first thing most people find out about me.

Which I really hate, to be honest: I don’t like seeming different, like people assume I’m some sort of saint. That’s not how I see myself. It’s not how I want others to see me.

On top of that, every time someone asks me why I donated (which is always), I never really know what to say.

It’s not that I lack for explanations. I’ve dissected my decision to death. The explanations I give tend towards the clinical—causal factors explicating my aberrant behavior. I’d had anesthesia before; I overemphasize abstract reasoning and principles; I went to Catholic school; I have a savior complex, etc.

That doesn’t include the jokes I tell because explaining makes me nervous: “I was a corporate lawyer and wanted the time off.”

But that just list traits like I’m talking about someone other than myself. Mix that with the humor, and it’s just a way to pretend I’m in the same spot as my interrogator: “I know it’s weird too.”

That hides the way I really feel about it, hides my earnestness. I gave because if I didn’t someone would die. None of my other reasons matter.

It didn’t need to be my responsibility. No one’s ever obligated to be a kidney donor, to anyone, for any reason. I chose to take that on myself.

For most donors, giving a kidney fulfills a need closer to home – saving the life of someone they care about. But there too, I think an essential step is to assume a responsibility that you have every right to walk away from—choosing to voluntarily burden yourself with the needs of another; choosing to answer that need by sacrificing of your own body.

We live in a transactional culture where we’re told always to put yourself first. Don’t take on burdens that aren’t yours. No one’s entitled to your help. Look out for number one.

That makes discussions about giving an organ really difficult. It feels like people often take living donation as an indictment of their own choices—if you don’t know whether you’d give a piece of yourself to save a friend’s life, does that make you a bad person?

Of course not. No one needs to take on obligations that aren’t theirs. But, for me, the choice to accept responsibility enlarged my own life, made it richer with purpose. Becoming a kidney donor was the best decision I ever made. It made me happier than anything else I’ve done in my life.

I’d wanted to donate for years. When I finally did, it felt like running my first half-marathon or graduating from law school. It was an achievement I’d deliberately planned and had to work to make happen, like summiting my personal Mt. Everest. I had gotten the chance to live out the best version of myself.

For many people, donation only deepens their sense of self—confirms the potential they knew they had all along. Many see it in practical terms: when someone I cared about was in need, I merely answered the call. They go back to their lives feeling joyous but largely unchanged.

That’s not what it was like for me. The experience turned out to be addictive. I had been working in a job that meant nothing to me besides the paycheck. Suddenly I felt drawn to a higher calling, though I didn’t yet know that meant working to end the transplant shortage. When I donated, I had set my mind and accomplished something profound. Now that I knew I had that power, I couldn’t just go back to the compromises I’d been making.

The road to where I’ve ended up was a long one. I tried to be a writer and failed at it. I left my home and the woman I lived with to start a new career in Toledo, Ohio. (I didn’t know anyone within two hundred miles). I received a grant, came back to the east coast, and started Waitlist Zero.

Ending the kidney shortage is my life. It wasn’t when I donated, but the same feelings that made me a donor then make me want to find everyone a donor now. The same things that make me uncomfortable telling my story as a donor keep me from speaking on my passion for Waitlist Zero.

Waitlist Zero means finding a transplant for everyone who needs one. It means that access to medical care shouldn’t be contingent on your skin color or your health insurance or how many friends you happen to have or how healthy they happen to be. It means that no one should ever have to feel the loneliness of wondering if anyone cares about you enough to save your life. It means tens of thousands of families each year shouldn’t have to go to someone’s funeral and wonder if they could have done more.

I wish I could say that this passion for ending the shortage was broadly shared but it’s not—for the simple reason that most people in the field don’t believe it’s even possible. Doctors are passionate about caring for their patients—incredibly passionate. But for decades the shortage has been growing and growing and the number of transplants has just stayed the same.

It gets tiring to hit your head against the same wall; after a while you forget that anything better exists. It’s hard to expect faith in the possibility for change.

But I do have that faith. It’s what sustains me through the travails of starting a new business and feeling sometimes like I’m making every possible mistake along the way. And I could give a dozen reasons why ending the shortage is possible: how living donation saves the government hundreds of thousands of dollars per patient; how studies show educating patients and their families can nearly double the rate of living donation; how if only one in ten thousand Americans donated each year, there’d no longer be a shortage.

Right now, six in seven people who need a transplant can’t find a living donor—I refuse to accept that six in seven Americans don’t have someone able and willing to save their life if only our community did a better job of supporting donation.

Yet those are just rational reasons. Ending the shortage is a transformational change: something more is needed than mere logical deduction. Otherwise it would have happened already.

What drives me to keep going is less rational certainty than the conviction that the field needs at least one person who believes the shortage can be defeated—the hundred thousand patients on the waiting list deserve champions who refuse to accept their deaths as inevitable. And we deserve a community where people take responsibility when they don’t strictly have to, a community that supports transplant and never lets die somebody who only needs a willing donor to live.

.

by Stephen Rice | Mar 10, 2016 | blog

Sedicah Powell is a mental health professional from New York. In 2014, life was intense. Good intense. She was working full-time and she’d just started graduate school at Fordham University to attain her master’s degree in Social Work. Then the news came. Her mom, who had been diagnosed with glomerulonephritis when Sedicah was in grade school, learned that her kidneys were now functioning at about ten percent of normal. She would need dialysis or a transplant right away. “When we got the news, it was a big crash in the family,” said Sedicah.

Coming together, her family decided that collectively they’d all be tested. Sedicah, along with her sister, grandmother, and aunt were all tested. “I’m African-American and many aspects of our health are not so great,” said Sedicah, referring to the fact that many African-Americans aren’t eligible to donate a kidney because of higher rates of obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes compared to other groups. “Because of these things, many of my family members were screened out. A few of us moved forward, but none of us were a match. This was another big shock.” she added.

Sedicah’s mom, Pauline would be a difficult match. She had a less common blood type, but tests also showed that she was sensitized, meaning her blood showed the presence of antibodies that would have reacted against a new kidney, causing a rejection. She would need a perfect match – someone with a compatible blood type but also naturally immune to Pauline’s antibodies.

The transplant team looked to plan B. Pauline’s results were listed in a paired exchange national database in the hopes of finding that perfect match. It was a numbers game. Months went by and no match. “We prayed about it. Prayer works. We prayed and prayed. We didn’t give up. We knew it was going to get better.”

Finally, a mother and son pair from the Bronx, and in the same situation provided an opening. Sedicah would donate her kidney to the other mom. The woman’s son, in turn would donate his kidney to Sedicah’s mom Pauline. The family’s prayers had been answered.

There was a solution at hand, but a new struggle had now begun. “Juggling all the other stuff was the hard part,” recalls Sedicah. “I had grad school classes to attend, papers to write, and full-time work.” Based on advice from her nurse coordinator at the transplant center, she planned to take one month off of work and school to recover, but how to make ends meet? She spoke with her boss who helped her make a plan. She’d use a week of accrued sick time and applied for a medical leave which allowed her to get short-term disability while she recovered. “The short-term disability helped, but it wasn’t the same as the normal paycheck,” said Sedicah.

After surgery, Sedicah described her recovery as short and painful. “I’m very self-reliant, but during recovery, I had to rely on others – even to get out of bed.” She was out of the hospital in 2 days and back to driving and school in 2 weeks. Because of the lifting constraints and active labor she performs at work, sometimes for 16 hours a day, Sedicah waited 2 months to return to work. But when she did, she knew she was ready.

Despite the hardships, Sedicah considers it to be a great experience. “I get chocked up every time I think about it,” she said. “The satisfying part goes without saying – not seeing my Mom suffer like she was. When I went into her [hospital] room, I was in pain, but she had this look on her face that I hadn’t seen for such a long time. She was smiling and her face was bright. I took part in something that saved my Mom’s life, plus helped save someone else who was sick. It completely changed two lives.”

Sedicah continues to give back by speaking in the community about donor awareness, participated in the 2015 NYC Kidney walk, and was given the “Gift of Life” plaque from New York State for her brave act. “When I speak to others, I always include the facts about African-Americans, and tell people ‘mind your health’! I never thought I’d donate a kidney at age 24. Healthy people of color should consider helping someone else in need.”

by Stephen Rice | Feb 18, 2016 | blog

“Why operate on a healthy person? Having been there, and seeing the improvement in my sister’s life, I think it was worth the risk. How often do we see a loved one suffering, and can actually do something about it?” — Charles Uzzell

Charles Uzzell is the youngest of five siblings. His older sister Monet’s kidneys had been failing for a while. The cause was a bit unclear. She’d had strep throat years earlier and doctors deduced that the streptococcal bacteria had caused damage to her kidneys. The cause, however wasn’t really the issue at hand for Charles, Monet, and the rest of their family. Monet needed a kidney and family members had spares.

Charles was the first to volunteer. “I had no trouble deciding,” said Charles. “But I appreciate the mixed feelings one has when deciding whether or not to give an organ. I am after all scared of needles and hesitant even to give blood.” He owned a Montessori school at the time and felt that he had the flexibility and good health needed to step up for the family. After being pre-screened as healthy enough to donate, he had blood drawn to see if he would be a compatible donor for his sister. Then he waited.

Charles was with his mom when the results came back. He was a perfect match! “This moment was the most emotional one of the whole thing. My mom and I both cried,” remembers Charles.

His sister was in California and he was across the country in North Carolina. He flew out to the west coast prior to surgery for evaluation testing including a procedure that, when described, scared him. The plan was to inject fluid into a leg and put a camera onto the kidney. “It turned out to be completely painless. I worried for nothing. This fact calmed me for the surgery.”

Pre-surgery, Charles felt “kind of goofy. Possibly too happy for the circumstances.” There was a woman in the bed next to him who was being prepped for a different sort of surgery, and was in a panic. “I was able to comfort her a bit and calm her down. This was a distraction for me.”

After surgery, he awoke to find his mom and another sibling in the recovery room with him. “I often sympathize with Mom because she had two kids in surgery on the same day,” said Charles.

This was May, 1994. Living kidney donation surgery was still being done using the open nephrectomy procedure. The less-invasive laparoscopic procedure used today was still being pioneered, making his recovery period longer and more painful. But, on the second day after surgery, he was able to walk down the hall and visit his sister. “She was doing great! My big fear was not that I would die, but that the transplant might fail or the kidney would be rejected,” said Charles. Despite some drug dosage issues that were still being sorted out, Monet had few surgery-related difficulties.

Charles’ total recovery time was about six weeks. After being discharged from the hospital, he spent two weeks at his sister’s house recovering before flying home. “Something that was very touching was that a volunteer drove me from the hospital,” remember Charles. “She continued to be involved in this small way.”

Twenty-two years after surgery, both Charles and Monet are doing well. “My sister is alive and happy. This was the best part of donating my kidney. Does that need to be said?” They celebrate the anniversary of the transplant every year. “My sister sends me music. It’s a little thing, but it means a lot to me and a lot to her.”

His advice to people like his sister considering a transplant it is, “be grateful, take your medicine, and stay healthy. Take care of your gift.”

His advice to others considering becoming a living donor is to “definitely do it. The kidney is fresher. That sounds weird, but this will be the best possible option for the recipient. It will make a huge impact in their lives. It takes them off of life support.”

Charles adds one last thing. It’s a complete miracle that humanity can do this. It’s just remarkable. To the medical profession – keep up the good work, I appreciate it.”

We appreciate you too, Charles.

by Stephen Rice | Feb 17, 2016 | blog

WaitList Zero occasionally publishes guest blog posts written by members of our community in the hopes of sharing viewpoints from various perspectives.

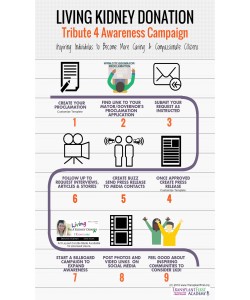

THE LIVING KIDNEY DONOR – TRIBUTE 4 AWARENESS CAMPAIGN

By: Risa Simon

Risa Simon, Founder and CEO TransplantFirst Academy

As a recipient whose life was profoundly changed by a living kidney donor, I’m deeply baffled by the absence of recognition for living kidney donors. I’ve spent countless hours trying to reconcile the magnitude of what I and many others have received. And though I know this has never been about a fair exchange—even if that were possible, my heart (and new kidney) are constantly seeking moral balance.

Last year, my creative mind conjured up a unique and simple way to deliver a small, but recognizable, improvement. The notion was to shed new light on our life-saving heroes who save lives by choice, not by death or medical necessity. The idea was to respectfully recognize their act as one of the highest levels of service humanity has to offer.

As the founder of the TransplantFirst Academy, I set out to seek input from other organizations in this space and received an overwhelmingly positive response. This prompted our organization to become the foundational force behind what is now known as: The Living Kidney Donor – Tribute 4 Awareness Campaign.

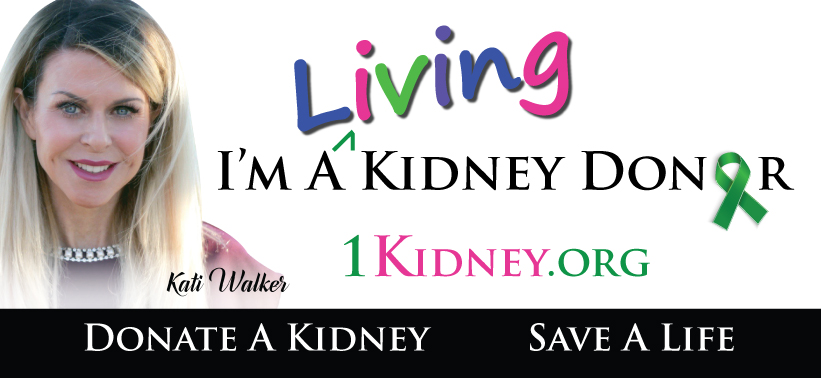

Our first target was to establish recognition for living kidney donors in the city of Phoenix. We achieved this status after the Mayor of our city signed a proclamation formally honoring living kidney donors for their brave life-saving acts. Our next target was to expand message visibility. We did this by launching a community outreach billboard campaign.

Our goal became two-fold.

Our main objective was to showcase the proud faces of living kidney donors and thank them for their life-saving service. Yet we didn’t stop there. We had a bigger plan, which was to inspire communities to join our movement to increase awareness in living kidney donation and inspire admirers and potential followers. Soon our standalone “Thank you for your service” initiative blossomed into a campaign that increased awareness and desire for others to personally contemplate this brave act for themselves.

Since living kidney donors don’t wear a Medal of Honor or a superhero’s cape, it’s hard to admire or emulate what they’ve done. Their decoration of a few scars is their only discreet distinction of lifetime achievement. Surely, we can give these brave champions more recognition for the role they played in saving lives.

Our nation’s organ shortage supports this campaign as a great call to action. Currently, nearly 10,000 people die prematurely or become medically disqualified for a kidney transplant every year. To add insult to injury, the number of people waiting on the list grows by 30% each year, as more sick patients face the same reality of need. The grim fact is that every year only 16 percent of the 100,000-plus waiting will receive their much needed replacement kidney.

Those who are fortunate enough to receive the gift from a deceased donor typically wait 5 years. Though there are some patients who are lucky enough to receive a kidney in a shorter amount of time, there are many more who wait much longer. Age also matters now. Many patients over the age of 50, who were approaching the top of the list after years of waiting, have lost their place in line due to new deceased-organ allocation.

This is just one of the many reasons living kidney donor transplants hold unparalleled value. Yet, until we can increase awareness and the numbers of living kidney donors (which has dropped significantly, including a 33% drop in 2015), we won’t be able to positively impact the futures of those in need.

This Campaign begins to address our moral obligation to do more. It starts by saluting those who courageously saved lives – and it keeps on giving by inspiring potential donors who might otherwise be unaware of this opportunity. Of course, living kidney donation is not for everyone. It takes a very special person to lean in this direction and a person in good health to medically qualify. To date, over 133,000 people have

been able to save an equal number of lives. These remarkable individuals give new meaning to the expression “Giving of self.” Let’s recognize these heroes and inspire a “heart-string” of potential followers.

If you are moved to join this campaign by expanding this project in your own city, we applaud your interest and welcome you aboard. If you are a recipient who has received the gift of life from a living

kidney donor, or a person who knows someone who has; or you are someone who believes in this initiative, take the first step now. You can do that by requesting a Living Kidney Donor Tribute 4 Awareness proclamation from your Mayor or Governor’s office. Often times a simple online search can lead you to that process.

You can also start to form a committee to help you explore billboard opportunities. Know that you don’t have to go it alone. Campaign art and special rates may be available. Check with the TransplantFirst Academy to learn more. Together we can achieve more, so let’s not let another day go by without taking action. It time to recognize those who courageously save lives and inspire others to become more caring and compassionate people.

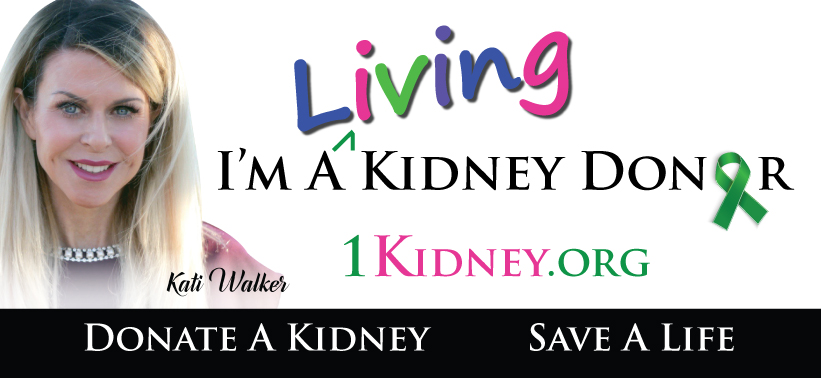

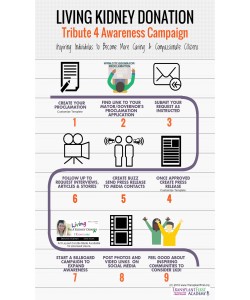

Not Sure Where to Begin?

Not Sure Where to Begin?

The infographic provides a 9 step snapshot to help steer your campaign. You can also visit this link for more information: www.TransplantFirst.org/campaigns-projects. For those who believe in this movement and would like to make a financial contribution to keep this campaign alive—please visit this link: www.TransplantFirst.org/contribute.

About the author:

So those are [some] of the specific initiatives that make up this evolving strategy. But what do we use to hold this strategic initiative together; what is the glue that keeps us focused and moving in the right direction? My answer to the question is our Core Values that we live and work with. And I wanted to focus on a Core Value central to transplantation; that is altruism. It is interesting to consider that altruism is the requisite catalyst for every single transplant we do. That single fact creates a stark contrast to almost all other transactions in our media driven world where egoism, the direct opposite of altruism, seems to Trump all; sorry for the pun!

So those are [some] of the specific initiatives that make up this evolving strategy. But what do we use to hold this strategic initiative together; what is the glue that keeps us focused and moving in the right direction? My answer to the question is our Core Values that we live and work with. And I wanted to focus on a Core Value central to transplantation; that is altruism. It is interesting to consider that altruism is the requisite catalyst for every single transplant we do. That single fact creates a stark contrast to almost all other transactions in our media driven world where egoism, the direct opposite of altruism, seems to Trump all; sorry for the pun! the transplant literature regarding altruism appropriately revolves around donors. Deceased donors, donor families and living donors alike, selflessly volunteer to make life-giving gifts to others, known or unknown, with no real identifiable benefit except the personal satisfaction of helping another. It is truly remarkable. But I want to challenge all of us to look at altruism in a much broader and simplistic way than most bioethicists and medical anthropologists commonly do.

the transplant literature regarding altruism appropriately revolves around donors. Deceased donors, donor families and living donors alike, selflessly volunteer to make life-giving gifts to others, known or unknown, with no real identifiable benefit except the personal satisfaction of helping another. It is truly remarkable. But I want to challenge all of us to look at altruism in a much broader and simplistic way than most bioethicists and medical anthropologists commonly do. and clearly enunciated set of Core

and clearly enunciated set of Core

Not Sure Where to Begin?

Not Sure Where to Begin?

Recent Comments